By Reed V. Horth, for CBPMag.com and Robin Rile Fine Art

When I was growing up, my parents were not “artsy” in the sense that we had a piano in the corner, took weekly trips to the local museum and collected Picassos. However, both were art-oriented in that they enjoyed art, stressed it in our family education and leaned to art as a vehicle to both educate my sister and I. I like to think that they saw value in broadening our cultural horizons beyond the small upstate New York town which we hailed from.

As I grew and traveled, I created a career in the field of art. But, those indelible memories of upstate New York persisted. One of my earliest and favorite books which I remember from my youth permeated every level of art lover that I have become…The book contained the illustrations of American master Maxfield Parrish (née. Frederick Parrish, 1870-1966).

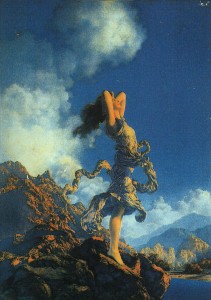

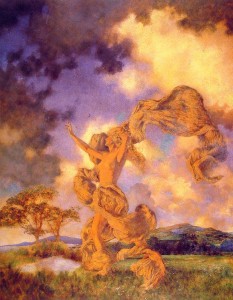

Parrish’s neo-classical paintings created a sense of atmosphere in worlds that might not exist in reality, but were what one might dream paradise to look like. Equal parts Hudson-River-School landscapes (such as the works of Cole, Bierstadt, Turner, Durand, etc), and Norman Rockwell’s narrative flair, Parrish wove intricate mythologies and dramatic literary characters into his original works, crescendoeing in the 1910s-1930s (“The Golden Age of Illustration”). Parrish began illustrating children’s stories, including L. Frank Baum’s “Mother Goose in Prose” (1897), Eugene Fields’ “Poems of Childhood” (1904) and the traditional tale of “Arabian Nights” (1909), among many others. He later illustrated magazine covers for Hearst’s, Colliers and Life and well as advertisers such as Wanamaker’s, Colgate, Oneida Cutlery and Edison-Mazda lamps. His pioneering use of photographic projection, color glazes, varnishes, oil colors, and transparencies, achieved an ethereal, otherworldly environment which his characters inhabit and influenced his contemporaries to attempt similar techniques.

Leafing through that hefty tome and mimicking Parrish’ style were some of the first memories I had of truly loving art.

****

On a recent business trip, I found myself at the St. Regis Hotel (2 East 55th Street) in New York City, to research a project on Spanish master Salvador Dali (who lived there off and on throughout the 1960s and 1970s), on whose walls were created some of his greatest masterpieces. To the left of the main lobby, on a nondescript wall, sat an original canvas from Maxfield Parrish entitled, “The Child Harvester” (1896). Stunned, I stared intently at her as denizens of the hotel scurried past and wondered why I was so rapt by her gaze. She silently and serenely peered at me as if catching her in the midst of her chores. The gold-leafed halo crowning her head served as a reminder that divinity can be found in hard work. As I was in a hurry, I quickly snapped a photo and went about my business elsewhere in the hotel, never forgetting that this was the first Parrish I had ever experienced in the flesh.

Vowing to return as soon as possible, I remembered that the St. Regis in New York was home to the massive, seminal “King Cole” mural by Parrish which it housed in the eponymous bar. This was one of Parrish’s most famous works and was frequently depicted in the books littering my youth. The whimsical Old King Cole from the nursery rhyme was “a merry old soul, and a merry old soul was he”. His servants milled about purposefully, but seemed to be frozen in a moment of uncomfortable shock. The momentary snapshot of the king stuck with me throughout my life. As Parrish grew up a Quaker, he was reluctant to paint the work given that the intention was to be housed in the bar of the now-defunct Knickerbocker Hotel. His patron, John Jacob Astor IV (1864-1912), who famously died aboard the Titanic in 1912, was never one to be told “No”. So, in 1906 Astor paid Parrish the “Kingly” sum of $5,000 for his efforts (which is approximately $132,000 in today’s currency). After the Titanic disaster, Astor’s heirs inherited both the Knickerbocker and the St. Regis Hotels, and long with it, the “Old King Cole” painting. With the later conversion of the Knickerbocker into an office space, the massive 8 foot by 30 foot (2.43 meters by 9.144 meters) “Old King Cole” painting was moved into the St. Regis bar space in 1932, where it became the focal point to one of the most exclusive bars in all of New York. When royalty came to New York, they dined with King Cole. When the New York Rangers won the Stanley Cup in 1994… their ring ceremony was conducted a few feet from the King’s watchful gaze. And, as my wife would repeatedly point out… it was a place where Anne Hathaway’s character receives the unpublished manuscript to the 7th Harry Potter book in “The Devil Wears Prada”.

Therefore, this was the bar that neither of us could miss visiting on our next trip to NYC.

Last week, to decompress after ushering clients and vendors during the Art Basel Week in Miami Beach, my wife and I decided to take a few days off to visit New York City. After ice skating in Central Park (a must for a former hockey player like myself), we strolled over to the famous St. Regis edifice at 55th Street for a cocktail. Passing the luxurious dining area we bandied ourselves into a seat facing the King Cole Bar. Parrish’s masterpiece dominates the space, spanning the entire length of the recently-renovated bar area. King Cole rakishly smiles, surveying us as subjects to his rule, receiving council from his fools. His guards, minstrels and his chef blush, aghast in the audaciousness of the fool’s candor…. The minstrels stop…. The chef blanches. The children at his feet stare vacantly ahead, rapt. It is indeed a merry sight which we would muse about and discuss throughout the evening.

Old King Cole was a merry old soul

And a merry old soul was he;

He called for his pipe, and he called for his bowl

And he called for his fiddlers three.

Every fiddler he had a fiddle,

And a very fine fiddle had he;

Oh there’s none so rare, as can compare

With King Cole and his fiddlers three.

~William Wallace Denslow, English, 1708-1709

We came to learn that the masterpiece recently underwent a massive restoration, coinciding with the $400,000 renovation of the entire bar area and the greater $35M effort to update the entire hotel. The famous bar served as the backdrop for famous scenes in movies such as “The Godfather” and “The First Wives Club”, as well as a frequent haunt for luminaries such as Salvador Dali, Ernest Hemingway, Marlene Dietrich, Marilyn Monroe and Joe DiMaggio and John Lennon and Yoko Ono. However, its most resolute resident was in dire needs of a bath. Decades of dirt, nicotine and alcohol needed to be painstakingly removed by a team of restorers from Rustin Levenson Art Conservation Associates in Chelsea. Given the response from the staff and guests whom we spoke with, the results were night and day.

Thanks to their cleaning, Parrish’s impish faces effervesce in the light where they previously seemed dull and lifeless. Whites shone as pure as a snowy December walk through Central park and each of the colors were saturated with the vitality which befits the merriment it was meant to instill. Instead of the dreary haze which had created a stodgy atmosphere in the bar, the revitalized image luminesces and brings life to the space. Parrish’s faces, which are now crystalline and clean, are typically modeled his own caricatured expressions and those of his few friends and family. However, in this instance, he used the visage of John Jacob Astor IV himself as the jovial king overseeing his empire. Given the princely sum paid for the work, it is only fitting. Parrish often stared into mirrors for hours on end trying to capture an expression which evinced just the right amount of humor, without becoming too un-serious as to belay his craft.

Thanks to their cleaning, Parrish’s impish faces effervesce in the light where they previously seemed dull and lifeless. Whites shone as pure as a snowy December walk through Central park and each of the colors were saturated with the vitality which befits the merriment it was meant to instill. Instead of the dreary haze which had created a stodgy atmosphere in the bar, the revitalized image luminesces and brings life to the space. Parrish’s faces, which are now crystalline and clean, are typically modeled his own caricatured expressions and those of his few friends and family. However, in this instance, he used the visage of John Jacob Astor IV himself as the jovial king overseeing his empire. Given the princely sum paid for the work, it is only fitting. Parrish often stared into mirrors for hours on end trying to capture an expression which evinced just the right amount of humor, without becoming too un-serious as to belay his craft.

We asked the bartender for whisky for me and a Red Snapper (the original name for the Bloody Mary, said to have been invented at this very bar in 1934, by bartender Fernand Petiot) for my wife. We chatted with locals and made friends with staff and patron alike. The more I sat gazing at King Cole and his subject, the more I was transported back to those moments of merriment as I thumbed through mom and dad’s book of Parrish paintings. I then mused and my own good fortune to be here in his presence.

In that instant, my life came full circle and I began to laugh. For, at that bar, in that space, the waiter confided in us the secret as to the source of both the King’s merriment as well as the pained expressions from the guards, chefs and minstrels in the painting….

In that instant, my life came full circle and I began to laugh. For, at that bar, in that space, the waiter confided in us the secret as to the source of both the King’s merriment as well as the pained expressions from the guards, chefs and minstrels in the painting….

None other than the kings occasional flatulence.

…A Merry Old Soul indeed.

…A Merry Old Soul indeed.

Reed V. Horth, is the president, curator and writer for ROBIN RILE FINE ART in Miami, FL. He has been a private dealer, gallerist and blogger since 1996, specializing in 20th century and contemporary masters. www.robinrile.com

All content ©2013 ROBIN RILE FINE ART. Any unauthorized reproduction of images, text or content is strictly prohibited.