Several years ago, a well-respected art dealer with whom I have known for some time brought me materials he had been given by another broker describing an oil painting from the famed Dutch master Peter Paul Rubens. The work was fantastic and carried an extensive and prestigious lineage which included The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and other luminaries of art collecting over the past two centuries. As the asking price was several million dollars, I felt it necessary to conduct significant leg-work prior to mentioning it to any of my clients as the research to independently verify works of this magnitude often takes quite some time. I did not doubt this dealers knowledge or professionalism but I am a natural skeptic and have spent far too many years entrenched in the art world to know the importance of properly researching a work such as this. The clients with the tastes for a great 16th century masterwork are broad indeed, but the circle becomes infinitely smaller when you seek those with wherewithal and means to make such a purchase. Therefore, as the group is small, you must be incredibly careful with presenting only works which can be independently verified, vetted and authenticated. One wrong move at this level can end you on the wrong side of a mediation panel, or worse… a pair of hand-cuffs.

After a few well-placed phone calls, an archivist in the Metropolitan Museum was kind enough to dig through their basement files on my behalf. There it was found that this painting was not by Rubens, but by Gaspar de Crayer (1582-1682) a contemporary of Rubens whose work is well regarded but considerably less expensive. Though comparable in technique, age and beauty, this work was actually valued in the low hundred thousands, quite a difference from the millions of dollars it was currently being presented at. Introducing clients to works such as these without due diligence and research could have been a very serious problem down the line had someone purchased it, but luckily the work was shelved and my friend’s reputation was not compromised.

This story highlights potential problems with a growing proliferation of brokers whose profession has less to do with the art itself and more to do with being a middleman in a daisy-chain of art brokers. In many of these transactions, there is less of an emphasis placed on scrutinizing the information provided and/or maintaining the integrity of the work itself and more on letting as many people know about the deal they have access to. In real estate sales, this kind of mass exposure may be advantageous, as a general rule of thumb states that the greater amount of people know about the property, the greater the chance of a sale. In the field of investment level art however, over- exposure of artwork can have an negative affect as works can be “shopped” if too many dealers present it openly on the market. Private sellers often want very few other dealers or brokers involved in this process as marquis works can become diluted. While this dilution could create a stigma around a work of art that may be unjustified, there have been many instances of artworks that fail to sell because their appearance of rarity has been compromised.

Additionally, problems can also begin to arise when many of these artworks and associated paperwork are scrutinized by professionals, authenticators, appraisers, foundations, museums and often the clients themselves who, after years of collecting, become seasoned to the artist’s works. Ideally a thorough knowledge art history along with extensive resources should be a prerequisite for art brokers, but oftentimes these “runners” have little knowledge of the intricacies of art and know even less about nuances in provenance, or lineage, of a piece of art. When it comes to investment level art, being a good salesperson is not enough and simply presenting a work as a “Rubens”, “Picasso” or “Dali” does not make it so.

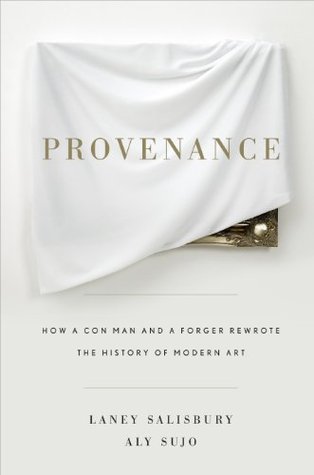

While contracting and exclusivity issues create problems with perfectly good pieces of artwork becoming spoiled on the market, bad works are just as much an issue for buyers, dealers and brokers as well. In the 2009 book “Provenance: How a Con Man and a Forger Rewrote the History of Modern Art” co-authors Laney Salisbury and the late Aly Sujo highlight the case of notorious English con man John Drewe and artist/forger John Myatt who developed not only fantastically convincing fakes of major 19th and 20th century masterworks, but also convincing histories and provenances that traced back to the archives in London’s Tate Gallery archives. This tome provides a sobering glimpse into how works from Alberto Giacometti, Ben Nicholson, Georges Braque, Nicolas de Staël and others became falsely archived in the Tate and the havoc wrought by having nearly 200 fakes thrown onto the market by prominent auction houses (including Christie’s & Sotheby’s), private and public galleries and a network of “runners”.

What can you do to protect yourself?

– First, go with your gut. Whether you are working with a broker or a fine art professional, always understand that if a deal does not pass your “sniff-test” it might just be too good to be true.

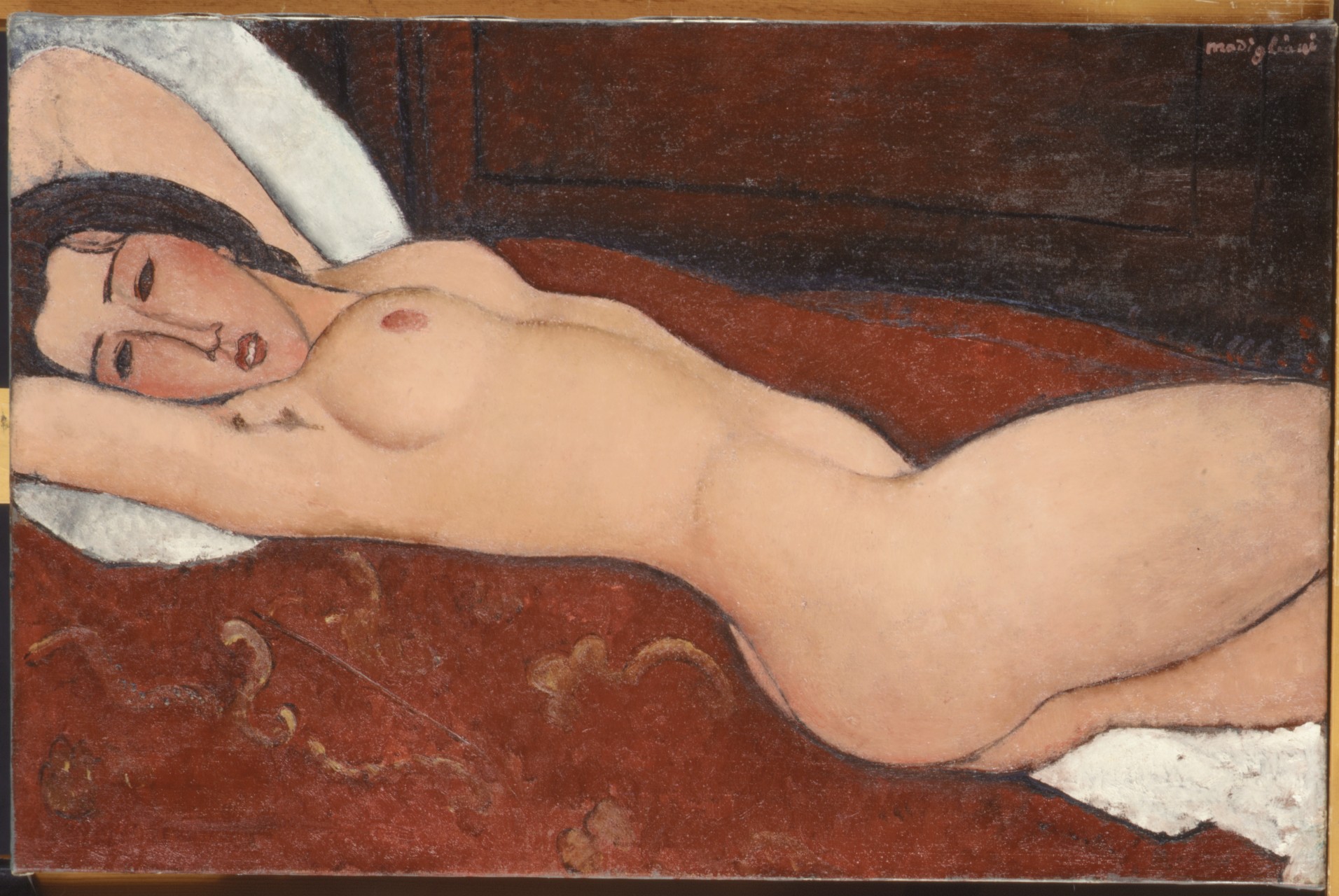

-Be a skeptic. (NOTE: I am presently working on a column which highlights the importance of certificates of authenticity for serialized works) It is important to know the origin of the works you purchase particularly if the artist is deceased. This lineage of purchase is called “provenance”. Oftentimes, prominent artists will have foundations, archives or experts dedicated specifically to cataloging their authentic works. Oftentimes, these foundations or other respected arbiters will compile a comprehensive listing of all the works an artist produced. This is not without its own difficulties as opinions vary and a lot of money is at stake if a work is excluded from a catalogue. This fact was made patently obvious to Marc Restellini whose oft-delayed catalogue raisonne of the paintings of Amodeo Modigliani for the Wildenstein Institute has given rise to death threats, lawsuits and public derision by owners whose works will not be included within its pages. In fact, the most respected guide to Amodeo Modigliani’s work was produced in 1958 by Ambrogio Ceroni, and it was so incomplete that it required updating in 1970 and 1972 to amend omissions and remove faulty works.

– Talk to a professional who has no vested interest in whether or not you obtain a work. If you call your local gallery to verify a work for you, he or she may be inclined to distance you from a work based on meeting their own sales goals. Independent authenticators and licensed appraisers can issue independent, third-party advice without the filter of self interest. Appraisers from the International Society of Appraisers, the Appraisers Association, or the Art Experts may be able to provide an independent evaluation on whether or not a work is sanguine. Museum curators and independent authenticators can provide you arms-length advice on individual purchases you are considering.

– Work with people you trust. As with every business transaction, form relationships with reliable partners. Talk to their partners and obtain references. Reputable brokers and dealers with strong ethics will often have a bank of referrals to call to edify you about their past work in Art or their chosen field. “Runners” may not scrutinize the works with this same ferocity, nor will they probably produce references to back up their reputations.

There is no fool-proof way to protect yourself in every transaction, as we all found out with the IRA bust which coincided with the stock crash. Seemingly “safe” investments became worthless and risky stocks went through the roof. Always make the best decision you can with the information you have. But also be aware of who you are speaking with and understand their motivations in the process. This way, you are at least on even ground and can make an informed decision.

All Content Ask Your Art Advisor: Caveat Emptor (C) 2016, Reed V. Horth, for Robin Rile Fine Art