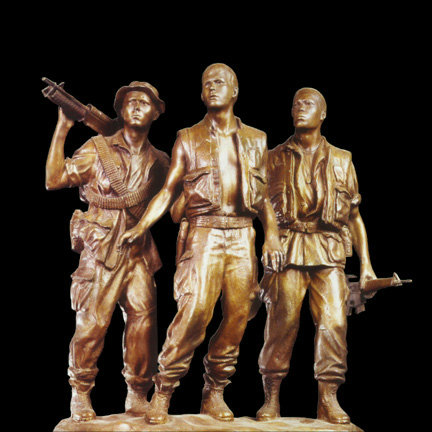

Three sets of eyes drink in the sight of a veritable ocean of names. 58,195 names inscribed in inch tall letters typeset over the expanse of a wall that, while it starts minutely on one edge, expands to over 10 feet tall (3 m) at its apex. Its length is overwhelming, stretching for 246 feet (75 m) and it envelops the viewer as if it could drown us. Three sets of eyes keep vigil morning, noon and night, through winter’s harsh snows and summer’s unbearable heat. The three sets of eyes belong to Frederick E. Hart’s (1943-1999) “Three Soldiers”. The wall they stare at is the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington DC.

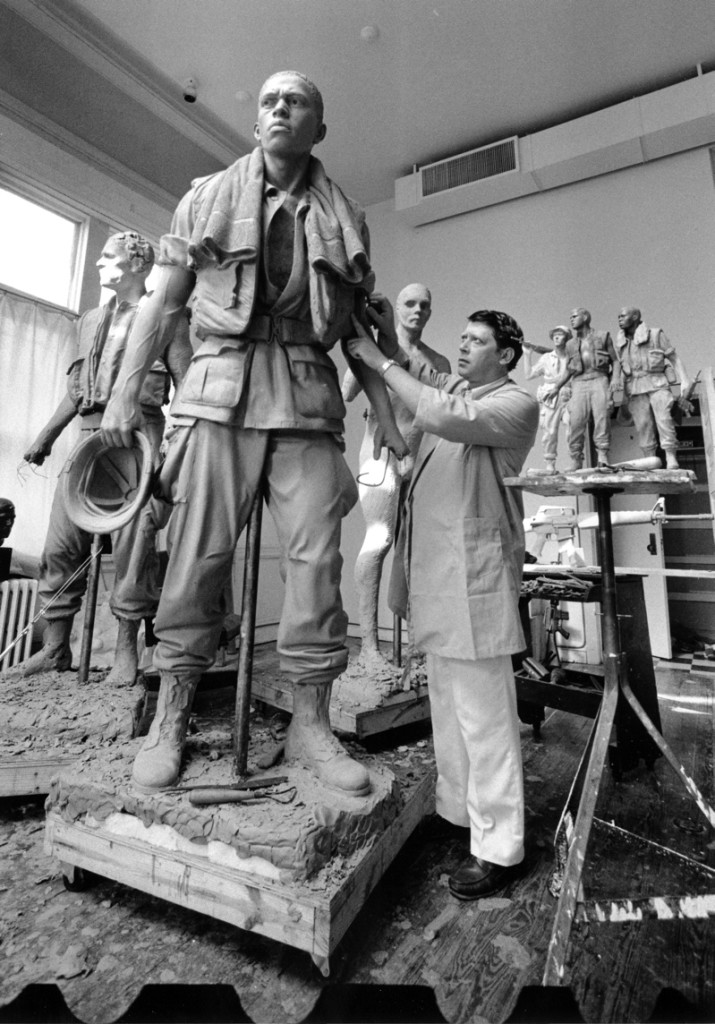

Hart’s depiction of three young American servicemen was rendered with such clarity and subtlety that it created what has been called “the most successful ensemble monument in the world”. Each of the men stand taught and at the ready, but also apprehensively seeing into the distance. The lieutenant’s slightly out turned hand motions his charges to stop. They turn to look with him and listen for his guidance. Their eyes are fixed into the distance as if scanning the horizon for a threat. Each of the men’s taught musculature and articulated weaponry stands at the ready for quick and decisive action. The three sets of eyes represent what is the best in all of us… diligence, spirit, humility, duty and in all cases… Sacrifice.

| “The portrayal of the figures is consistent with history. They wear the uniform and carry the equipment of war; they are young. The contrast between the innocence of their youth and the weapons of war underscores the poignancy of their sacrifice. There is about them the physical contact and sense of unity that bespeaks the bonds of love and sacrifice that is the nature of men at war. And yet they are each alone. Their strength and their vulnerability are both evident. Their true heroism lies in these bonds of loyalty in the face of their aloneness and their vulnerability.” ~Frederick Hart |

**************

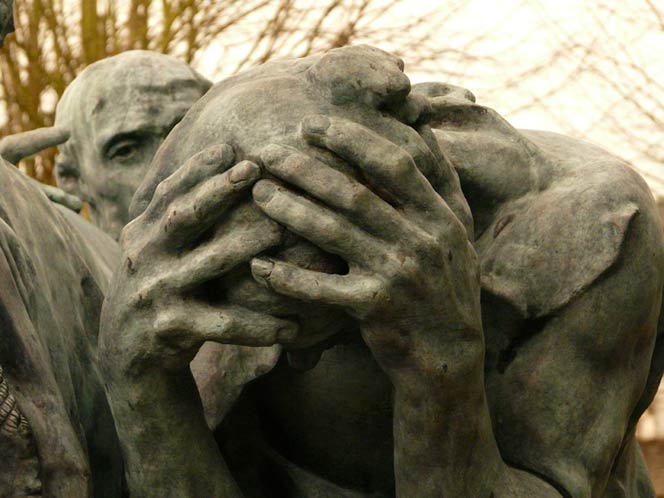

The spirit of sacrifice is also sculpturally evident generations apart and half a world away, mirrored the faces of six individuals in Northern France. Traditional depictions of these individuals, collectively known as the “Burghers of Calais”, had shown them to be defiant, courageous and steadfast. French master Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) turned convention on its ear by taking academic sculpture and imbuing it with an honesty and organic-nature that had not been seen before. Rodin’s “Burghers” were all too human, vaguely prideful but agonizing about their martyrdom to the hands of the English King Edward III in 1347. The city of Calais was besieged by Edward III’s forces for over a year, pushing the population to the brink of starvation. Edward offered a compromise that he would halt the siege if six of Calais’ most prominent citizens surrender themselves to him for execution. Eustache de St. Pierre, one of the city’s most wealthy citizens, volunteered followed by five others. Their willingness to sacrifice themselves for the good of their populace became legendary and stayed the hand of the English king who, consequently allowed them to live. Rodin depicted them as they would have been, in a mixture of fear and defiant self-sacrifice. Wearing only rags and nooses limply hanging about their necks, they prepare to exit the city with its ceremonial keys. Their hollow eyes are open and their hands hang mournfully. Their oversized feet are move slowly as if trapped in a morass of tar and time. The sad depiction humanizes the subjects and brings them eye to eye with present day viewers, allowing them to commune with the past the way few sculptures had before, or since. However, the initial reaction to them allowed little by way of acceptance. “We were called to the old town hall of Calais to look at the sketch [modele] of the burghers of Calais that M. Rodin had just brought. It is sufficiently studied to give a good idea of the effect intended by the artist, and all of us felt a slight disappointment. We did not imagine our glorious citizens going to the camp of the king of England that way. First, their depressed attitude shocked our religious feelings, and we felt that the work we were looking at, far from glorifying the devotion of Eustache de St. Pierre and his companions, only produced the opposite effect.” -report by the Calais committee on the commission.

Rodin and Hart both courted controversy in the commissioning of their respective works. Rodin dealt with a public scornful of less-than-patriotic looking heroes, and Hart navigated the turbulent political terrain which bridged both overt racism and the skirmish between modern sculpture and figurative classicism at the end of the 20th Century. Heavy nationalism and hyper-sensitivity to each subject heightened the effect of each sculpture on their respective populaces. After the humiliating defeat Franco-Prussian war in 1871, France went through a period of intense political self-flagellation which transcended literature, music, architecture and all of the arts. Similarly, the bruises of Vietnam were still fresh in the minds of soldiers, politicians and the public at large when Maya Ying Lin’s (American, b. 1959) minimalist Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall was initially erected. Given Lin’s ethnic-sounding name (she is an American, born to Chinese parents living in the US) the public decried her monument as a great “black gash of shame”. A compromise was struck in which Hart was to commissioned to erect a figurative element overlooking the wall itself. In time, the congruity of elements and the dissipation of time have led to the public acceptance of the monument and wall working in unison.

Years later, Hart would again revisit the theme of martyrdom as he paid allegorical homage to the daughters of Czar Nicolas II of Russia, Anastasia, Tatiana, Olga & Maria, who were killed during the Bolshevik Revolution in 1918. Hart called them “The Martyrs of Moderndom” as they represented all of the beautiful things which were somewhat forgotten in the 20th Century, “The ability to have Faith, sustain Hope, feel the transforming power of Beauty and revel in the Innocence around us”. Faith, Hope, Innocence and Beauty, the four “Daughters of Odessa”. This was Hart’s clarion call to return to our classical antecedents in all of the arts, music, poetry, film and literature. Just as their predecessors the “Burghers of Calais” and the “Three Soldiers”, the “Daughters” are depicted as an ensemble, with each figure boasting their own breadth and idiosyncrasy. Each is lightly draped in ethereal linens of the spirit realm. Their faces are at peace and depict the youth and vitality of their allegorical counterparts, Hope, Faith, Innocence and Beauty. Whereas the “Burghers” and “Three Soldiers” courted controversy, the “Daughters” were eagerly accepted for permanent placement at the Prince of Wales’ private garden at Highgrove upon their unveiling in 1997.

Frederick E. Hart (American, 1943-1999) “Three Servicemen Maquette” (1983)

TEXT © 2012 Reed V. Horth, for ROBIN RILE FINE ART